ESG

Pricing Carbon: What Are The Options?

Putting a price on carbon emissions makes polluting energy sources expensive and provides an incentive for emitters to reduce them. That's the theory. What it looks like in practice is assessed by the head of investment strategy at RBC.

With carbon dominating discussions, it is crunchtime at the COP26 summit in Glasgow. But what carbon market mechanisms are already in force and how reliable are they in bringing emissions down in meaningful ways? Author Frédérique Carrier, managing director and head of investment strategy at RBC Wealth Management, examines the landscape, explaining how mandatory carbon pricing is put into practice, either through cap-and-trade regulations or a carbon tax. She also looks at the viability of voluntary carbon offset programs, which critics regularly scorn for letting the worst laggards off the hook. There is a lot to take in here, and it is a good time to revisit these market approaches to see where they are succeeding or need reforming. As Carrier points out, a main focus of COP26 in the final week is pricing carbon. How then should investors take this new business expense into account?

The editors are pleased to share these insights and invite readers to respond. The usual editorial disclaimers apply to contributions from outside organisations. To comment, email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com and jackie.bennion@clearviewpublishing.com.

Putting a price on carbon emissions

Increasingly, countries are making pricing carbon emissions

mandatory, either by enforcing cap-and-trade rules or by imposing

a carbon tax. But with the pace of government regulatory support

varying dramatically from country to country, many companies are

also trying to offset their emissions voluntarily, in response to

the growing cohort of environmentally-conscious consumers and the

increasing influence of environmental, social, and governance

(ESG) funds.

How should investors take this new business expense into

account?

For investors, it means that this additional cost of doing

business from emitting carbon, should be taken into account. We

explore how mandatory carbon pricing is implemented, either

through cap-and-trade regulations or taxes, and explore some

popular voluntary carbon offsets.

Focus at COP26

The 26th UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), in Glasgow, this

week, is widely regarded as the most important climate conference

since the 2015 Paris conference, which gave rise to the Paris

Agreement. Ratified by close to 200 nations, the Paris

Agreement’s goal is to keep mean global warming well below 2

degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). To achieve this,

signatory countries will need to decrease emissions by close to

50 per cent over the next decade—an enormous challenge. A main

focus of COP26 is carbon emissions' pricing.

Putting a price on carbon emissions makes polluting energy sources expensive and provides an incentive for emitters to reduce them. The concept is based on the increased recognition that the cost of emitting carbon dioxide (CO2) should be factored into the cost of production by emitting companies, much like a chemical company that dumps harmful residues in a river or landfill, causing health problems for people who live nearby, should be accountable.

Mandatory pricing of carbon emissions

An important feature of the mandatory carbon pricing is that

carbon emissions must not only be priced but also become

increasingly costly over time. Some countries are making pricing

carbon mandatory either through cap-and-trade regulations or

through carbon taxes, while some, such as Canada, use both. By

putting a price on carbon emissions, US companies using an

internal carbon price, including Microsoft and Mars, say it helps

them to drive low-carbon investment, energy efficiency, and seize

low carbon opportunities.

Increasing momentum for cap and trade

Cap and trade refers to legally binding regulations that cap

total emissions and allow companies to trade their allocations.

Cap and trade is not a new approach; it has been used to tackle

environmental problems in the past. Putting a price on sulphur

dioxide (SO2) emissions, introduced under the Clean Air Act, is

largely credited with helping to solve the acid rain problem in

the 1990s.

Cap and trade has grown in importance, albeit slowly. There are more than 60 cap-and-trade programs in operation across four continents in jurisdictions making up 54 per cent of global GDP and covering 16 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, up from less than 5 per cent 10 years ago according to the International Carbon Action Partnership.

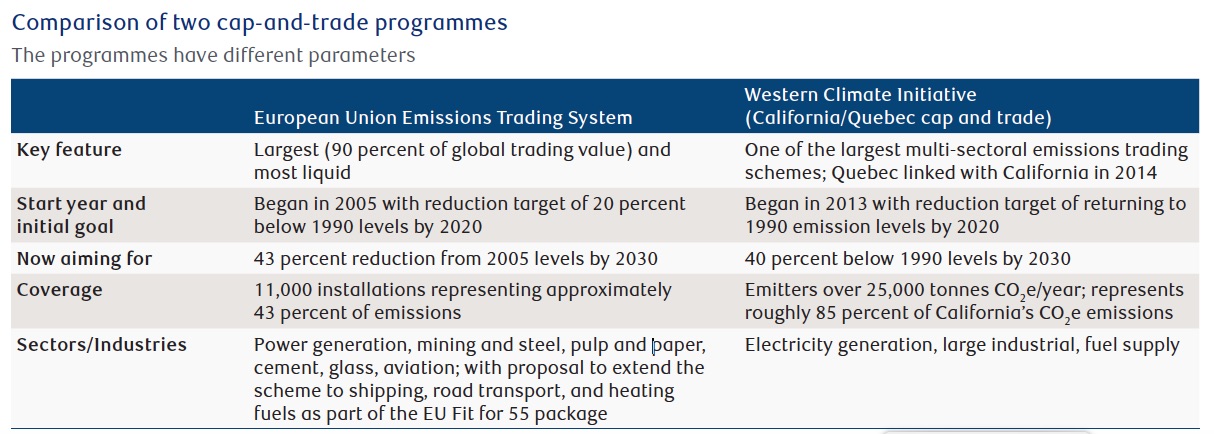

The most developed programs are regional. The EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) established in 2005 remains the most liquid. Beyond this, a number of countries, provinces, states, and cities operate a cap-and-trade program.

The US is home to the Western Climate Initiative (to which Quebec is also a signatory) and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative for 11 East Coast states, while the UK stopped participating in the EU’s scheme by launching its own program. Promisingly, in July 2021, China launched a nationwide program focused on the thermal power industry, which accounts for 40 per cent of the nation’s emissions. China is responsible for over 25 per cent of global emissions, compared with 11 per cent for the US and 6.4 per cent for the EU 27 (excluding the UK), according to the Rhodium Group.

With the US returning to the Paris Agreement and China establishing its own emissions trading program, most observers see a growing momentum for cap and trade as an effective mechanism for driving a meaningful reduction in carbon emissions.

How does cap and trade work?

By assigning a price to a damaging activity, cap-and-trade rules

provide companies with a financial incentive to reduce emissions

by themselves. All cap-and-trade programs set emissions' limits

compatible with their nation’s CO2 reduction targets and

calculated by governments and policymakers. Typically, these

limits, or caps, decrease gradually over time toward a

predetermined reduction goal.

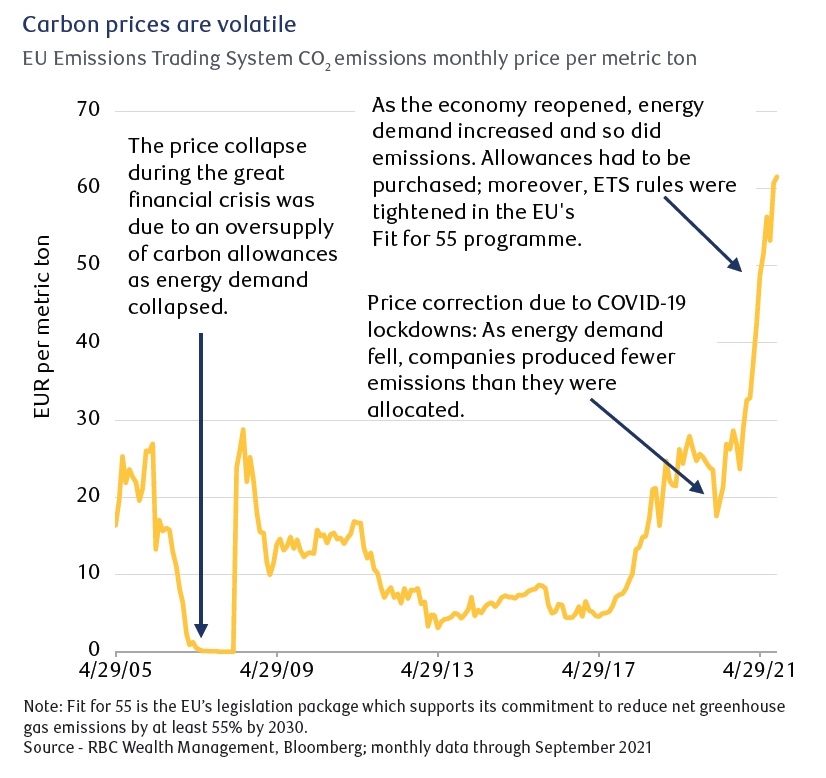

Pricing volatility

Carbon allowances or units totaling up to this maximum are then

allocated or auctioned to companies in high-emission sectors,

such as power generation, oil and gas refining, steel making, and

chemical manufacturing. Each allowance permits the emission of

one tonne of CO2. Inclusion of these high emitters in the

cap-and-trade scheme is mandatory and regulated.

The allowances are tradable commodities. They can be bought and sold in the secondary markets, where banks and trading companies provide liquidity. This sets the market price for carbon.

If a company generates emissions over what it has been allowed, it needs to buy more carbon units from the market, thus incurring a cost. But if the company generates less than its allowance, it can sell any excess units in the market to a company that hasn’t successfully reduced emissions. Alternatively, it can hold its unused allowances for future use.

The price of carbon is determined by supply and demand. Supply of units is set by regulators to decrease annually, leaving the price of carbon to rise or fall depending on whether firms produce emissions above or below their allowances.

Prices for carbon emissions differ across all the various cap-and-trade programs worldwide. The price of carbon emissions within the European plan reached €65 per metric tonne in September 2021. By contrast, the price of a similar amount within the California/Quebec cap-and-trade program was less than $28 at the same time. The difference occurs because each program covers different industries and is designed to meet different carbon emission reduction goals, etc.

RBC Capital Markets expects that carbon prices will rise over time, pointing out that as the cap declines, the market supply of allowances should get tighter. The International Monetary Fund is of the opinion that prices must rise significantly to stimulate alternative or low-emission options. It estimates that at a global level, a price of $75 per tonne or more is needed by 2030 to restrict global warming to below the Paris Agreement’s well below 2°C (3.6°F) threshold.

Proponents of cap and trade point out that it gives companies flexibility by allowing them to hold allowances into future compliance periods. As a result, reducing carbon emissions can become a multi-year decision. Cap and trade also tends to be viewed more positively by consumers/voters than carbon taxes.

Some countries with high carbon prices are considering putting a charge on the carbon content of imports from regions without similar schemes. To this end, the EU in particular is pondering a carbon border adjustment mechanism.

Carbon taxes

Carbon taxes are another way of implementing a fee on CO2

emissions. Governments set a price per tonne of carbon emissions

high enough to provide an incentive to switch to clean energy

technology such as wind, solar, or other non-carbon-emitting

power sources. Moreover, the tax usually goes up over time. In

Canada, the carbon tax is set at CA$40 per tonne of CO2

equivalent for 2021. The government recently updated its federal

carbon pricing benchmark, setting a minimum carbon price of CA$65

per tonne in 2023, rising to CA$170 per tonne by 2030.

A carbon tax differs from a cap-and-trade scheme in that a tax provides a high level of certainty about future prices—as those are set by the government in advance—but not about emissions. Cap and trade, by contrast, provides visibility about future emissions—as decreasing limits are set—though the price is left to market forces.

Taxes can be more equitable to the extent that they can be applied to all CO2 emitters, either industrials or individuals, through a fuel tax as opposed to cap and trade, which assigns a cost only to industrial CO2 emitters.

Unsurprisingly, taxes are not popular with the electorate. President Joe Biden’s proposal of a carbon tax was vehemently opposed, causing him to opt for a payment scheme for emission reductions. In the UK, fuel taxes have not been changed since 2011. Furthermore, taxes can be watered down, making them a less-effective tool. In 1992, a carbon tax was discussed by the Clinton administration but was watered down to a negligible tax on gasoline.

Cap and trade and carbon taxes need not be mutually exclusive. RBC Capital Markets, LLC director of Commodity Markets Anthony D’Agostino points out that Canada, for instance, has both mandatory policy instruments in place: British Columbia imposes a carbon tax, Quebec and Ontario have cap-and-trade programs, while Alberta has implemented a hybrid system that combines a tax with a cap for large industrial emitters.

Voluntary carbon offsets

Regardless of government mandated-schemes, an increasing number

of companies wish to reduce their carbon footprint or accelerate

the process of achieving net zero emissions. RBC Capital Markets

estimates that over 20 per cent of global corporates are

targeting net-zero emissions by 2050 or sooner.

Their motivation varies: management might be climate-conscious, or want their company’s shares to be appealing to ESG funds whose importance is growing and could represent as much as 60 per cent of mutual fund assets by 2025, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Management may also want their company’s products to be appealing to consumers who are increasingly demanding greener product solutions. Green consumer preferences are well entrenched in Europe. A 2020 study by IBM and the National Retail Federation found that nearly 70 per cent of consumers in the US and Canada think it is important for a brand ro be eco-friendly.

Companies that are not in a cap-and-trade jurisdiction and wish to reduce their carbon footprint or accelerate the process of achieving net-zero emissions can buy carbon offsets. They are certificates that represent one metric tonne of CO2 equivalent that is either prevented from being emitted into the atmosphere or removed from the atmosphere as the result of energy-efficient projects such as reforestation or production of renewable energy. By using carbon offsets, a company can balance out its carbon footprint. Carbon offsets are also available to individuals: most airlines offer travellers the opportunity of offsetting the carbon footprint of their flight.

Reforestation is a common offset, as trees absorb CO2, they grow and store it, and makes up half the voluntary market. Other offsets include wind and solar farm projects that replace coal-fired power plants, thus preventing CO2 emissions, providing energy efficiency improvements.

McKinsey, a consulting firm, points out that though the voluntary carbon credit market is currently experiencing significant growth, it is still relatively small. It estimates that it could be worth some $50 billion by 2030 as demand grows.

Critics claim that many of these projects are ineffective, and do not reduce emissions as they claim to. Reforestation projects, for example, are often undertaken in faraway locations, where land is cheap and, if left unmonitored, may not be successful.

As a result, offsets are cheap compared with the price of carbon on cap-and-trade schemes, at a lowly $3 per tonne. Still, Easyjet, a UK low-cost airline group, which carried close to 100 million passengers before COVID-19, spent £25 million or six per cent of pre-tax profits to offset the carbon emissions from the fuel used on all its flights on behalf of its passengers.

Others point out that carbon offsets are less efficient at tackling climate change. Companies, they suggest, should focus on actively reducing emissions, not merely offsetting them. RBC Europe Limited, energy analyst Al Stanton thinks that to slow down and ultimately reverse climate change, technologies and solutions that actively remove CO2 directly from the atmosphere need to be deployed.

Peering into the future

Whether a country has a legally binding cap-and-trade program in

place or not, more and more companies are incorporating a cost

for emitting CO2 as a way of measuring their climate change risk

and putting their businesses in a better position for managing

the transition to a lower carbon business model. A McKinsey study

highlights that ‘some companies are setting an internal charge on

the amount of carbon dioxide emitted from assets and investment

projects so they can see how, where, and when their emissions

could affect their profitability and investment choices.'

Meanwhile, some US financial services companies are using

internal carbon pricing to identify low-carbon, high-return

investment opportunities.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards

Board

Of the 2,600 companies that report their emissions to the Carbon

Disclosure Project, 23 per cent were found to be using an

internal carbon charge, and another 22 per cent plan to do so

over the next two years.

French company Danone (Evian bottled water and Dannon yogurt), publicly reports its carbon-adjusted earnings per share, which has grown faster than its regular EPS as a result of the company’s reduced carbon intensity.

US companies using an internal carbon price, including Microsoft and Mars, say that it helps them to drive low-carbon investment, energy efficiency, and seize low carbon opportunities.

Broad investment implications

Politicians of all factions are under increasing pressure to

introduce green regulations. In 2020, the Grantham Research

Institute at the London School of Economics counted close to

2,000 pieces of climate legislation across the world, of which

two thirds were enacted since 2010. The Securities and Exchange

Commission may not adopt Europe’s strict Sustainable Finance

Disclosure Regulations, but it may choose to include relevant

climate disclosure in its regulation.

Whether a company is bound by a mandatory cap-and-trade regulation, subject to a carbon tax, or whether it uses carbon offsets, more and more companies will incorporate the price of carbon into decisions about the way in which they operate and invest for the future.

RBC Global Asset Management’s head of global equities, Habib Subjally, observes that, in his experience, companies that understand how they may be exposed to or affected by climate change and have planned to deal with or take advantage of that exposure (or with other ESG issues) are usually better managed in most other respects and are superior creators of long-term value for their shareholders.

We suggest that there are two useful paths for investors. They could seek to manage risk by developing an understanding of how individual companies in a portfolio may be exposed to carbon pricing or climate change in general. It should be possible through stock selection and diversification to manage the associated risks down to acceptable levels.

In almost every sector, US companies using an internal carbon price, including Microsoft and Mars, say it helps them to drive low-carbon investment, energy efficiency, and seize low carbon opportunities. In almost every sector of the equity market, companies that develop solutions to reduce carbon emissions or in some other way enable other businesses or consumers to mitigate this issue are likely to emerge.